Fed up with the violent conflict that has recently engulfed their country, musicians in the west African nation of Mali have come together to call for peace. More than 40 of Mali’s most talented musicians gathered in the capitol city of Bamako to record a song for peace and unity called “Mali Ko” (which means “For Mali”). They collectively call themselves the Voices United for Mali.

The song’s lyrics state, “It is time for us artists to speak about our Mali. Malians, let us join hands because this country is not a country of war. Don’t forget that we are all of the same blood. The only way out of this crisis is the way of peace.”

“War has never been a solution,” the lyrics say. “We don’t want war! Not in our Mali! War destroys everything in its path. We want peace. Peace in Africa! Peace in the world!”

The project was organized by world-renowned singer Fatoumata Diawara, and includes Oumou Sangare, Bassekou Kouyate, Vieux Farka Toure, Djelimady Tounkara, Toumani Diabate, Amadou and Mariam, Khaira Arby, Kasse Mady Diabate, Baba Salah, Tiken Jah, and many others.

The purpose of the song is to remind Malians, both inside and outside of the country, of their power as a people united. Diawara says the song makes two requests: a plea for peace and a plea for the emancipation of women in Mali, because if there is jihad in their country, men will always be able to strike compromises with other men. It will be a lot harder for women.

Diawara explained, “The Malian people look to us,” referring to the country’s musicians. “They have lost hope in politics. But music has always brought hope in Mali. Music has always been strong and spiritual, and has had a very important role in the country, so when it comes to the current situation, people are looking up to musicians for a sense of direction.”

Music has played a fundamental role in Mali’s culture for thousands of years. Mali’s music planted the seeds for many of the music styles we listen to today, from Blues and Jazz, to Soul and Rock and R&B and Hip Hop. The desert blues of Mali is listened to around the world, earning Grammy awards and inspiring collaborations with Western artists, including the Rolling Stones, Carlos Santana, Robert Plant, and Bono. Perhaps more than anywhere else, music is the center of Mali’s culture, preserving its history while serving as a contemporary political tool.

“The multiethnic, multilingual display of artistry in “Mali Ko” is an inspiring reminder of another thing I’ve come to love about Malian society: its long history of peaceful conflict resolution and inter-group harmony,” writes Bruce Whitehorse. “Musicians always agree on looking for peace,” says Bassekou Kouyate, a Grammy-nominated musician from Mali and participant in Voices United for Mali. “We are not afraid of anyone.”

You can listen to the song from Voices United for Mali on their Soundcloud page.

Mali has been in crisis since last January, when Tuaregs in northern Mali began a separatist uprising, newly invigorated by an influx of fighters and weapons from Libya. A military coup by junior officers angry at how the government responded to the Tuareg uprising followed in March, leaving the country in disarray and hastening the loss of its northern half to insurgents. Islamist groups quickly pushed aside the secular Tuareg militants, taking over northern towns and imposing their strict interpretation of Islamic law.

Militants in the north of Mali declared Sharia law, and soon banned music (other than the traditional Islamic calls to prayer). In August this year, a spokesman for the group Ansar al-Din (Defenders of Faith) announced the ban on all western music, saying “We do not want Satan’s music. In its place will be Quranic verses. Sharia demands this.” The term “western music” is a blanket description for all forms of music: modern, traditional, foreign, and local. The result is that music has either disappeared or gone underground.

Meanwhile, almost all the musicians in the north have fled the country, most of whom languish in refugee camps in Algeria, Mauritania, Niger, or Burkina Faso. It is the biggest humanitarian crisis the Sahel has ever known. “There’s no music up there any more,” says Vieux Farka Toure, son of the king of the West African blues, the late Ali Farka Toure.

But the situation is also bad in the south of Mali. Many live music venues in the capital Bamako, such as Le Diplomat, where Diabate and his Symmetric Orchestra used to play every weekend, have closed. The same goes for hotels and restaurants, starved of their once plentiful supply of foreign tourists.

“People use what they earn to feed themselves, not to have fun,” says Bassekou Kouyate. Musicians in the south of Mali are unable to work at the moment as clubs have been closed, public concerts have been postponed, and there are very few weddings taking place. Kouyate said, “The government is nervous and afraid of terrorist attacks on public gatherings. They are asking everyone to wait until the situation in the north has calmed down.”

Rokia Traore, one of Mali’s most famous international stars, says that “without music, Mali will cease to exist.”

In Malian society, music anchors every ceremony, from births to weddings to prayers. Village bards known as griots sing traditional songs and poems of the desert, passing down centuries-old tales, as well as their community’s history. Many Malian musical traditions are derived from the griots, who are known as the “Keepers of Memories”. In this manner, memories were preserved from generation to generation, along with ancient African traditions and ways of life.

In current times, lyrics serve as a source of inspiration and learning, and as a way to pass down morals and values to youths. They have also been used to expose corruption and human rights abuses, and have helped eradicate stigmas and given a voice to the poor. Mali is considered one of the best places in the world for music lovers and performers.

“Music regulates the life of every Malian,” says Malian musician and producer Cheich Tidiane Seck. “From the cradle to the grave. From ancient times right up to today.” National Geographic states that, “Music is at the heart of life in Mali, intrinsically connected to everything.”

“In northern Mali, music is like oxygen,” said Baba Salah, one of northern Mali’s most-respected musicians. “Now, we cannot breathe.”

Musicians in Mali are fighting back. The war in Mali is being waged on two very different fronts. In the north, the military operations continue, with French-led troops retaking towns from Islamist rebels. Meanwhile, a cultural offensive is taking place, in which Mali’s celebrated musicians are hitting back against the Islamist imposition of Sharia law and the banning of music.

“Mali has been a shining light of African culture and especially music, because of the seamless fusion of traditional with modern influences combined with a tolerant cultural environment. The tradition can be traced back to the days of the Mali Empire, where griots sang the praises of kings and noblemen. That rich musical history is now threatened since Islamists overrun the north of the country and turned off the music, literally,” writes Billie Odidi for Africa Review.

The current conflict has threatened music throughout Mali, forcing the renowned Festival in the Desert to go into exile. Festival director Manny Ansar is among those speaking out against the music ban and in support of his country’s culture. “Music really has a special place in Malian society,” says Ansar. “It’s more power than law. It’s a kind of social law, sometimes more strong than the political or social law. Everything is transmitted in Mali through music, through poetry.”

Manny Ansar adds that “it’s through our music that we know history and our own identity. Our elders gave us lessons through music. It’s through music that we declare love.”

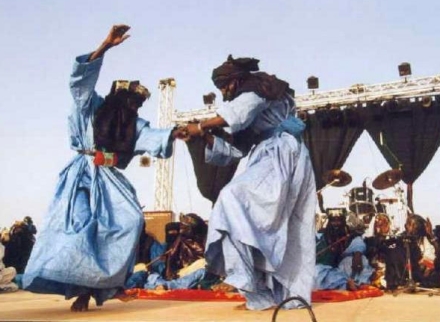

Festivals have always been a part of the Tuareg’s nomadic lifestyle, providing a place to share stories, race camels, stage sword fights, settle scores, make policy, and play music. For centuries these gatherings have provided an invaluable opportunity for the nomadic tribes to meet and celebrate with various forms of song, dance, poetry, games, and other ancient cultural traditions.

The Festival in the Desert was founded on the Tuareg (Tamashek) tradition of nomadic clans meeting up in the cooler dry season, to celebrate their culture, their music, and their stories from their year’s wanderings. Over the years, the Festival In The Desert has branched out to represent all the communities and extraordinarily rich musical traditions of the desert, of Mali, and of the region as a whole. It is one of the most unique and respected music festivals in the world.

The main purpose of the festival is to promote peace through music by bringing people together, regardless of origin and religious beliefs. The festival was an example of how music and art can transcend differences and find common appreciation. The festival showcases the diversity and the mutual tolerance that’s always been a fundamental part of Mali’s musical culture.

The Festival in the Desert was started in 2001. It was initially envisioned in the 1996 event “Flame of Peace,” in which 3000 guns were publicly burned to signify the beginning of the reconciliation between the nomadic and sedentary communities of the southern Sahara.

From 2001 to 2008 the festival was located at Essakane, a remote oasis village northwest of Timbuktu. The area is covered in rolling white sand dunes, and surrounded by rocky hills. Because of growing insecurity in the area, the festival has been held at the ancient city of Timbuktu since 2009.

The Festival of the Desert is Mali’s number one tourist attraction, bringing people from around the world together for three nights of communal celebrations in the beauty and simplicity of the desert outside of Timbuktu, a city founded over the centuries on the trade of goods and ideas between the north and south. It is cited by many as one of the world’s top 25 festivals.

The festival features musicians from Mali, Mauritania, Niger and many other countries. “It is Africa’s version of Woodstock, Coachella, and Burning Man all combined into one spectacle, an experience not to be missed,” described an American visitor.

Cultures of Resistance attended the Festival in the Desert in 2009, and produced a short video called “Playing for Peace in the Sahara”. They describe how “in the Malian desert, musicians meet to build mutual respect by sharing cultures. Artists share their music and dance to emphasize what they have in common, rather than what separates them. This short film highlights the event’s approach to promoting cross-cultural expression as a means of overcoming the threat of divisive conflict.”

The 2013 edition of the Festival in the Desert will be a touring Caravan of Peace, called the Festival in the Desert in Exile. It will be a caravan of artists promoting peace and national unity in Mali, travelling from Mauritania to Mali and onto the Tuareg refugee camps in Burkina Faso. The caraval will last from February 7th to March 6th 2013. It begins in Kobeni, Mauritania (15 km from the border with Mali) in the southern Sahel desert. On February 14th they join the Festival of Segou in Segou, Mali. And on February 16th they join the Festival of Mali in Bamako, Mali.

February 20-22, the traditional three days of the Festival in the Desert, will take place in Oursi, Burkina Faso. Then at the beginning of March, they will join the International Festival of Selingue in Selingue, Mali.

They state that, “Despite our present ‘exiled’ status from Timbuktu, in proud nomadic tradition, we will embark on a 2013 caravan of artists, fans, and festivals uniting for Peace, Tolerance, and Human Dignity. The tour will begin in the Sahel region of Africa, and then travel internationally until we are able to return to our homeland in peace and freedom of expression.”

“As an ambassador for peace, internationally known Malian artist Oumou Sangare will lead a stalwart line-up of African musicians in one of two caravans that make up the 2013 Festival in the Desert in Exile,” writes Ariel Bleth for Ethical Traveler. The caravans will include artists from Morocco, Mauritania, Algeria, Niger, and throughout Mali.

“Peace and tolerance, now more than ever, has become an absolute emergency. This is the message we want to pass among ourselves first and then to others throughout the rest of the world who share with us the same values. The brute sound of weapons and the cries of intolerance are not able to silence the singing of the griots or the sound of the Imzad (violin) and the Tinde (drum),” say the festival organizers.

The Festival in the Desert is considered Africa’s top music festival, followed by Mali’s other big music festival: the Festival on the Niger, which was recently cancelled for 2013, and is being replaced by two components: an international gathering on “Culture and Governance”, and art exhibitions with a theme of “Peace and Social Cohesion”.

The organizers explained that in, “solidarity with our defense and security forces involved in the liberation of our country, the Festival on the Niger Foundation decided to turn the 9th edition of the Festival on the Niger into a special one, with the theme of “Cultures in Resistance for Peace and Reconciliation.”

It is not only music that is being threatened in northern Mali. Timbuktu is home to hundreds of thousands of Africa’s most treasured ancient manuscripts dating back to as early as the 11th century, and covering such subjects as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, grammar, agriculture, poetry, rhetoric, law, politics, philosophy, and theology. Most of the manuscripts predate the arrival of Europeans on the African continent, about the same time that the oldest universities in the English-speaking world, Oxford and Cambridge, were established. At that time, Timbuktu was a thriving intellectual city of more than 20,000 scholars, several universities, and hundreds of libraries. Timbuktu’s books and tombs have also been destroyed by the Islamist fighters.

But international attention has focused on the plight of Mali’s music, which has given so much to the world. The Glastonbury Festival announced Rokia Traore as the first named act on their 2013 line-up, with other Malian artists to perform each day. And there are concerts taking place around the world raising awareness of what is happening in Mali. As Traore warned: “If it can happen in Mali, it can happen anywhere.”